Most of us never question what happens to the things we throw away. Once something leaves our hands, it feels finished. But William McDonough, the architect who would later co-author the book Cradle to Cradle, was never comfortable with that ending. Long before the term ‘circular economy’ entered the mainstream, he was asking a quieter, more radical question: what if waste isn’t an unfortunate side effect of modern life, but a design failure we’ve simply learned to accept?

William McDonough’s career often gets summarized as ‘sustainable architecture,’ but the story begins long before sustainability became a discipline. Growing up in Japan and Hong Kong, he observed systems that operated on cycles: rituals that renewed themselves, systems that used everything, cities that regenerated without naming it ‘sustainability.’ Nothing was truly wasted; things became other things. It was an impression that stayed with him, even as he later trained as an architect in the United States.

By the time he began practicing professionally, McDonough was asking questions most designers weren’t yet asking. Why did buildings, products and materials have such short, linear lives? Why did we accept that the final chapter of nearly everything we create is a landfill? It wasn’t a question the architecture schools of the 1970s were prepared to answer. But McDonough kept asking it anyway. Because if the natural world knows how to design for forever, why don’t we?

Where others saw inevitability, he saw a design flaw.

By the 1990s, McDonough was no longer an emerging architect; he was winning awards and designing expansive, airy workplaces long before daylighting and wellbeing became industry metrics. But beneath the architectural language was a deeper intention: a belief that design could be a catalyst for industrial change, not just a way to package it.

He saw something most designers didn’t: the environmental crises of the time weren’t just policy failures or industrial accidents. They were design decisions made upstream. And if design created the problem, design could also rewrite the rules. This is the point where many architects would have settled for a few green roofs and called it innovation but McDonough did the opposite: he went deeper into the supply chain.

His conviction intensified when he met Michael Braungart, a German chemist working on environmentally safe materials. Together, they scrutinized supply chains, chemical formulations and manufacturing processes. What they found was a system optimized for efficiency, but not for long-term responsibility. Materials were designed without a plan for tomorrow. Products were built to be discarded.

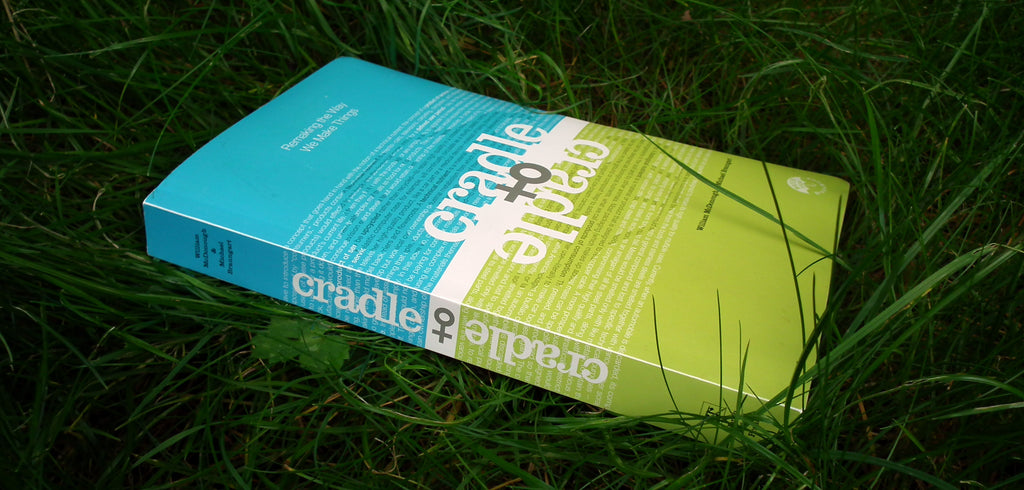

Their response came in the form of a book in 2002: Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. It was a book that didn’t simply propose recycling but rejected the very premise of waste. Products should not ‘end.’ Materials should not ‘downgrade.’ Impact should not be the cost of doing business.Printed on a polymer designed for infinite reuse, the book was a message wrapped in its own manifesto.

Rather than offering incremental improvements, the book proposed a fundamental shift, one where materials circulate like nutrients and ‘waste’ becomes an outdated concept. Industries read it with a mix of fascination and unease. This wasn’t another sustainability guide. It was a redesign of capitalism’s operating logic. Not exactly a modest proposal, but an industrial provocation.

The reception was immediate and international. Companies wanted guidance on how to shift from a linear model to a circular one. McDonough and Braungart formalized their work into MBDC (McDonough Braungart Design Chemistry), helping organizations redesign products down to the molecular level. Later, the Cradle to Cradle Products Innovation Institute established an independent certification system, translating the philosophy into measurable criteria.

While McDonough continued his architectural practice, the nature of his work expanded. Factories were no longer simply buildings but potential nodes in a regenerative system. Consumer products were not objects but participants in a material cycle. Even supply chains were reframed as ecosystems with interdependencies and consequences.

Some projects achieved exemplary results. Others revealed the complexity of changing entrenched industrial norms. McDonough has acknowledged these challenges openly, emphasizing that transformation is iterative. The aim is not perfection but direction, a continuous move toward materials and systems that give more than they take.

You can trace McDonough’s fingerprints through the rise of the circular economy movement, through material innovation labs at major brands, through global policy discussions on waste and resource cycles.

McDonough’s influence extends well beyond the design world. He has advised companies eager to reinvent themselves and sometimes those who weren’t, but needed to. His presence in a meeting is described by collaborators as equal parts architect, philosopher and systems engineer. He can zoom from a molecule to a metropolis without losing the thread.

What distinguishes his approach is its refusal to frame sustainability as sacrifice. Instead of asking people or industries to do ‘less bad,’ McDonough argues for designing systems that inherently generate benefits. Ecological, economic ánd social. This framing has resonated widely, offering a constructive narrative in a field often dominated by warnings and limits.

But not all his ideas have landed cleanly. Critics point out that Cradle to Cradle is difficult to implement at full integrity in messy global supply chains. Still, McDonough’s answer has remained consistent:

‘Yes. That’s why it’s called redesigning industry.’

The world McDonough anticipated decades ago is the one we live in now: a world negotiating resource limits, climate pressure and a growing awareness that ‘away’ does not exist. His core argument – that the future will be shaped not by what we take, but by what we design – feels less idealistic and more like a blueprint for survival.

He continues to work, teach, design and provoke. Not loudly and theatrically, but with the confidence of someone who has spent forty years following the same question: How do we make things that make the world better?

It’s a question that still doesn’t have a complete answer. But thanks to McDonough, we know it has a direction: we cannot solve the problems of today with the design logic of yesterday.

Florine started out as an art critic, but that turned out to not be quite her thing. So, she did what any sensible person would do - packed her life (and family) into a tiny campervan and roamed the planet for seven years. Now back in the Netherlands, she’s juggling life as a strategic advisor for a Dutch non-profit, while also writing for magazines and platforms. When she’s not typing away, you’ll probably find her treasure-hunting at thrift stores to jazz up her tiny house by the sea. Or wandering outdoors, because apparently sitting still isn’t really her vibe.

Subscribe to the monthly mindshift

Our very best, every month in your mailbox. Subscribe now and join the reloved revolution!